AWASH

Lena Ruth Soloworiginally published in June 2020

Issue 30

Essay

My uncle went to the hospital ranked fourth in the country when he had stage four cancer and one of the things they offer if you go to the hospital ranked fourth in the country is your family can have a consultation with the director of the family grief center after you die (even at the fourth best hospital in the country for cancer, you might die).

I make an appointment to call the family grief lady on my lunch break and walk down to the Hudson River. The family grief lady says because of my age I probably haven’t experienced a lot of death. I mumble a list and then say, “And I’m gay?” When she doesn’t respond I try to explain, “People I know die or want to die a lot I guess.” She chirps at me that grieving isn’t linear.

I tell her I’m struggling to come to terms with the reality of the constant presence of death. That I don’t know how to go on knowing it’s always more loss. That I used to think the specter of queer suicide was the reason I thought about death all the time but now I work with people older than me whose family members are dropping like flies and I don’t know how to sit with it. That even queer joy feels tinged with melancholy.

I tell her I had originally reached out for help around deciding if I should stay in my relationship which was falling apart and she says oh we don’t recommend making big life decisions when you’re in the throes of grief and I say oh well too bad because we broke up yesterday.

I stare at the water.

Once I read something about how we’re all so anxious because we always look at our phones and we never look at the horizon, so every once in a while I try to find a horizon to stare at. Sometimes it’s the Atlantic Ocean, sometimes it’s Jersey, , but still, I feel myself soothed.

Later I go to the bookstore with a list of books about grief and the guy helping me asks cheerily, “Ohhh, what’s the occasion?”

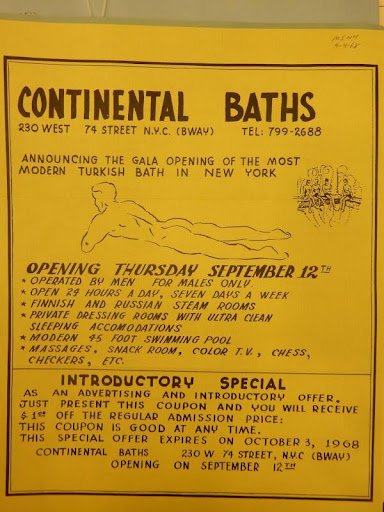

Later still I meet a girl who’s mapping all the old public bathhouses in New York City. She tells me that there were more than twenty bathhouses, all over the city, and shares black and white photos of men peering out from changing stalls, kids splashing. I scan the pictures for glimpses of my ancestors, who lived in tenements on the Lower East Side. This is stupid, because I’m sure I wouldn’t recognize them, but I’m desperate to find evidence they were there, soothed by the water.

Map of New York City’s public bathhouses

The girl tells me about a book called Washing the Great Unwashed and I can’t get the title out of my head. The girl likes to say, “Some things just stick in your mind.” When we walk around the city, she points out where some of the baths still stand — this one now a church, that one all boarded up — and, more tragically, where some of them used to be — here, a bank, there, new apartment buildings. I just learned of their existence but I mourn their loss.

Later, she sends me a picture of her flushed face post-bath and I tell her I want to scrub her hard with a stiff-bristled brush in the tub.

I am crazy about her; I am crazy about the baths. When things start unraveling, I am frantic. It’s hard to differentiate between heartbreak and grief — when someone dies I miss my exes, when a love affair ends I miss the dead. Loss on loss on loss — I feel heartbreak coming on and I don’t want to lose her; I don’t want to lose the baths.

I have a breakup ritual. Well I did something once and then I did it after another breakup, so now I call it a ritual.

The banya is a Russian bathhouse. A bathhouse is not a spa. It is not quiet or romantic. My breakup banya in Sunset Park is a single room with two pools, one hot and one cold. It’s musty and The Real Housewives is playing on TV. There are three wood-paneled saunas and old Russian men bring bundles of branches in to unceremoniously whack their own bodies. The Russian men don’t care if you’re weeping softly to your friend in the pool.

The best way to experience the banya is to push yourself right to the edge of what you can stand. It’s like the beach—lie in the sun til you’re so crispy you might scream, stand in the waves until they crash right on top of you. Sit in the sauna til you’re faint, then one more minute.

It’s likely that my ancestors went to bathhouses in the shtetls in the Ukraine and Belarus. There's no way to confirm of course. Still, I like to think of them sitting in the steam before I think of them all getting pogromed (another lingering death I suppose I could have mentioned to the family grief lady, but how do you say that sometimes you feel like you can hear your pogromed ancestors screaming “run!”).

Painting by Emelian Mikhailovich Korneev, 1812

My Jewish ancestors were probably pushing to the edge of their senses too, as it turns out. In 1113, Apostle Andrew, observing Russians in their bathhouses, wrote “After anointing themselves with tallow, [they] take young reeds and lash their bodies. They actually lash themselves so violently that they barely escape alive. Then they drench themselves with cold water, and thus are revived. They think nothing of doing this every day and actually inflict such voluntary torture upon themselves. They make of the act not a mere washing but a veritable torment.”

Voluntary torture. Veritable torment. Some things just stick in your mind.

My friend Kam is in divinity school and they say it’s just as important to claim a legacy of queer ancestors as claiming ancestors “by blood.” Our queer ancestors were fucking around in bathhouses too – more voluntary torture, this time a sweaty mess of cocks and cum and piss.

One of Kam’s favorite queer ancestors is the artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz. I don’t journal, but I do write emails to my exes that I never send. After seeing David at the Whitney, I write but do not send:

So many of these queer artists have their relationships so present in their work and I always wonder what was going on there. Like were David and Peter Hujar fighting all the time? They must have been. I think about our relationship in the lineage of queer relationships, which isn’t to romanticize either of them. Kind of de-romanticize I think – like sure you were muses but were you destroying each other? Were your friends worried? I realized that I also have this wiring in me about being so scared you’d die. Just all the time scared. That must be a queer lineage thing too right? Like all these people must have been so scared their partners would die.

It’s pedestrian, really, to indulge in the fantasy of everyone you know dying. Still, so many people have died – the first dyke I knew and the girl I tap danced with in college and Kevin my old cranky mentor. Each time, my fucked up brain tries to cope by making me cold and distant with people I love, preparing for what feels like the next inevitable loss. Maybe this is why queer people are so bad at taking space after breakups—it’s painful to be in touch but at least you know they’re alive.

When I can’t get to the ocean or the river or the banya, the regular bath will do. I am not precious about my bath. It is the utilitarian pleasure that I’m searching for, not a simpering “self-care” indulgence. When I can’t stop thinking about someone I love getting hit by a car, or my ex calling me a monster, or the bathhouses of New York disappearing one by one I mutter out loud, grimly, “Go get in the tub.”

I don’t unplug; my laptop and cell phone come with me (god forbid I actually allow an internal focus, instead I text lovers pictures of my tits and my toes). In what I’ve been told is a weird move, I sit in the tub while it fills up. I can’t stand to step in to the hot water so for a while I’m naked in a cold empty basin. I like to be in there as the water runs in, the sound reminds me of being underwater and my racing thoughts slow as the water rises.

Bath selfie courtesy of the author

It doesn’t always work. One night during quarantine I decide to use a bath bomb I’ve been saving – I drop it in the tub and it doesn’t fizz, just thunks to the bottom and starts to slowly seep an ugly orange powder. The water turns a putrid beige. I slam my hip into the faucet getting out and stop to kneel and cry for a moment.

Still, it’s an escape. I put myself in the bath, on the ferry, in the ocean, to think about how we keep each other alive. People I know used to say this a lot: We keep each other alive! And the thing is, sometimes we do and it’s beautiful. But sometimes we don’t, sometimes people die anyway. Or sometimes it’s not beautiful, sometimes we’re kept alive and we’re falling apart, or we’ve martyred ourselves so we feel needed, or we’re alive but we’ve destroyed relationships, friendships, communities. I can spiral into nihilism – like every relationship is doomed, like every person you love will die unexpectedly, like the world is going to burn faster than we can do anything to stop it.

I get back in the water to slow the frantic swirl, and I try to think about a different world. I think of a piece my friend M.E. O’Brien wrote for Pinko. In it, she builds on the writings of French philosopher Charles Fourier, who imagined sites of collective care structured as communes. The communes M.E. describes are of course not the isolated white-picket fences of suburbia, but they’re also not small queer collective houses where who does the dishes becomes the site of trauma. These communes are made up of 200 people, who self organize into smaller units without the pressures of adherence to biological family. M.E. describes a joyful space with collective canteens, libraries, and shared caretaking. I text M.E. in tears when I read her piece. This isn’t part of her description, but when I imagine these 200 person communes in my head, they’re built around water.

Achieving this communal vision requires neither overly self -sacrificial martyrdom, nor an intensely individualist approach to healing. To build this world we have to get out of the tub, sometimes. Call a friend, a coworker, a neighbor. Dare to dream that together, you could make something different.

When we imagine a utopian future we’re grieving, too, for the people who don’t make it there. But what is there to do now except imagine the world we might build? Remember what it’s like to go back to the ocean. Back to the bathhouse. Sit in the heat. Stand in the waves. Voluntary torture. Veritable torment. Remember what it’s like to hold your friend’s hand, to feel the thrum of excitement when you know you’re going to win, to kiss someone you love in the hot summer sun. Imagine a world where you can bathe with friends, lovers, and family; a world where we still exist with the ocean; a world where you’re allowed to mourn a death, a relationship, a movement; a world where there’s time to soak.

Lena Ruth Solow is a writer and union organizer living in Brooklyn. Twitter: @lenaruthsolow Newsletter: tinyletter.com/lenaruth